Should Rappers Lyrics Be Used Against Them On Trial? Author, Erik Nielson Explains In New Book

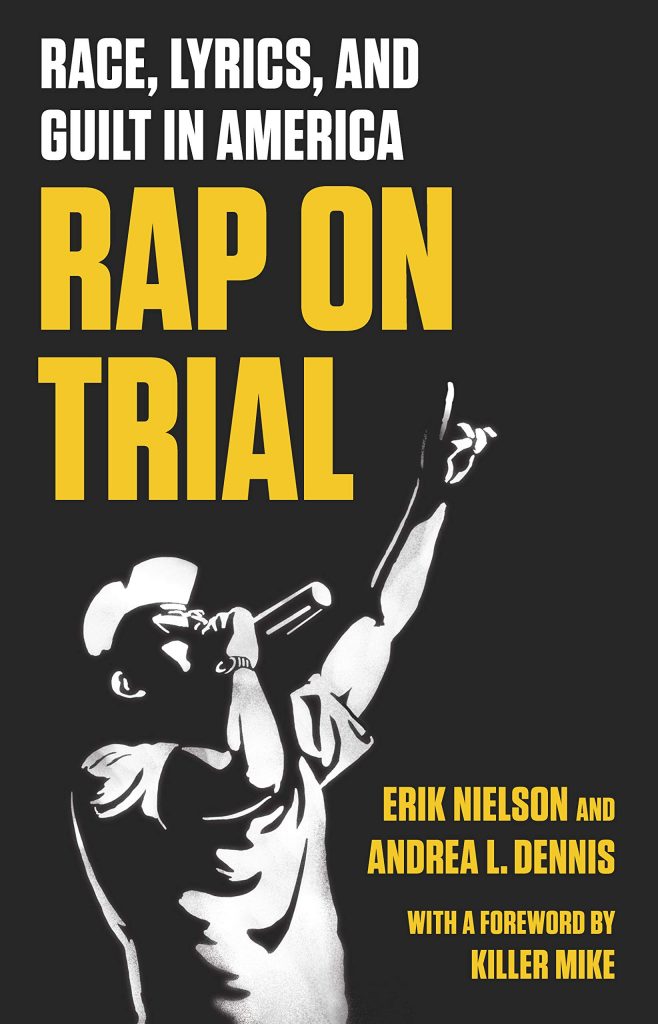

Author/Professor, Erik Nielson tackles the difficult question, should rap lyrics be used against rappers in a court of law in his new book, “Race, Lyrics, And Guilt In America: Rap On Trial.”

Erik Nielson is an associate professor of Liberal Arts at the University of Richmond where he teaches courses on African American literature and hip-hop culture. He has testified in court on trials involving rap lyrics being used against rappers as criminal evidence. Nielson feels it’s an injustice to use a person’s art or form of expression musically against them in a court of law. He recently released a book, “Race, Lyrics, And Guilt In America: Rap On Trial,” that tackles the issue head on. One trial in particular that caught, Nielson’s attention was, former No Limit artists, McKinley Phipps AKA Mac. Phipps was convicted of manslaughter in 2001 and is currently serving a 30-year sentence. A case in which his lyrics were heavily used against him during the trial. Not only does Nielson feel it was wrong that Mac’s lyrics were quoted for jurors, but he also feels they have the wrong man and he points to the evidence or lack thereof as the reason, Phipps should be a free man.

During our recent conversation, Nielson gives an overview of the book, explains how different genre’s are given a pass in court, but rappers aren’t and much more!

When did you first gain interest in hip-hop and what prompted you to look into rappers’ lyrics being used against them in court when they shouldn’t be used against them?

Erik Nielson: Those two things happened very far apart. My interest in hip-hop started when I was 11 or 12-years old. I was one of those suburban white kids who heard it and sort of gravitated to it. the first tape I ever heard was Run DMC; that’s mid to late 80’s. I was buying lots of it. I’ve been a fan my whole life at various points. Maybe for a few years I listened to other types of music more, but I have been a lifelong fan. So, my academic work focuses on African American literature and music. I started writing about hip-hop, specifically rap music several years ago because I wanted to, treat it the way that we treat other kinds of poetry. That’s not to say that all hip-hop songs or hip-hop lyrics are good poetry. Although many of them are. It’s just really just looking at it as the sophisticated and complex artform that it is. There weren’t a whole lot of people writing about it in that way. That’s what I started doing.

As I developed my research, I became interested in… really black art in the United States and law enforcement. So, when I started looking at that specifically in respect to hip-hop, that’s when I started to find what this book is about. I started to find that rap lyrics were being used as evidence in criminal cases. That’s obviously not the only way that police and law enforcement have targeted rap artists, but that’s the one that I found most surprising. Because the consequences were so severe, and it seemed cattily unfair to use somebody’s art to put them in prison.

Do you feel like it’s intentional to use their lyrics against them or do you feel some just can’t differentiate between expression and reality?

Erik Nielson: I think it’s both. I think for some people, it is just a genuine misunderstanding of rap music and the genre. Maybe people don’t like it, but I think for some people they don’t understand it. If somebody stands up in front of them, if a police officer for instance said, “Hey, rap lyrics are meant to be interpreted literally. So, this song is a confession and this song is evidence or motive.” If people don’t understand the genre and there is an authority figure telling them things about it, even if they’re being told it’s wrong, they’re going to believe it, so I think for some people it’s a lack of understanding. I think for other people though, it’s intentional. It is a willful misrepresentation of rap music by people who know better but are ultimately motivated to secure conviction; particularly if they don’t have a whole lot of evidence otherwise. They are willing to misrepresent the genre in order to put the artists behind it away.

The book is, “Race, Lyrics, And Guilt In America: Rap On Trial.” Tell us about it.

Erik Nielson: In 2011-2012, I really started looking at examples of where police and prosecutors were using rap lyrics in criminal cases. And at first it was the higher profile cases that caught my attention. The, Lil Boosie trial was one that I really started paying attention to. When I saw that and a few other examples here and there, I really started trying to compile a list of how many there were. Is this just happening here and there or is this more pervasive? I started doing that and I found very quickly that there were scores of cases all over the place. In fact, Boosie was kind of the exception because he was a well-known artist who could hire his own private attorney’s. What I found in most cases was that it was young amateurs who didn’t have name recognition and, in many cases, didn’t have the resources to defend themselves in court the way, Boosie did. I started investigating this issue, I started reaching out to attorneys. And through that, I started testifying in these cases as an expert, and I’ve done that a number of times in cases across the country, where after police and prosecutors have said ridiculous things about rap music to a jury, it’s my job to then sit there and tell the jury how it really is and explain the background of it.

So, I think the book… first off, it’s hard to write a book like this because the audience can be so different. Is it a book for hip-hop heads? Is it a book for some woman in middle America who doesn’t know anything about it, but she’s interested? Is it somewhere in between? So, what we do upfront is sort of just give an overview of rap music and where it came from and how hip-hop culture emerged. Some of the basic conventions of it. Lots of people hear the confrontational rhetoric of rap music. And they take it seriously and they take it literally. So, one of our goals is to show a sort of long history of this type of rhetoric and that it is a mistake to understand it that way. And really the rest of it is saying, hey look, this is happening across the country, it’s resulting in young men, almost all of them either black or Latino being thrown in jail, sometimes for their entire lives. In some cases, being sentenced to death and rap lyrics are playing a significant role in that. It’s really a sort of wake up and explaining the practice and offering some solutions. Some ways to move forward so that we can undo or at least slow down what is obviously a racist and unjust practice.

There have been rappers reach out to law enforcement with the hopes of forming some type of structure between the streets and law enforcement to build the community and it just never seems to go anywhere beyond the initial meeting. Is that something you think could bridge the gap or are we still a long way away from a solution?

Erik Nielson: That’s a good question. I would like to be able to imagine a day where hip-hop artists and police could work together in a sustained meaningful way to improve their communities. I do not however see that as likely anytime in the near future. That is driven far more by police than rap artists. Police have long held this antipathy towards rap artists, whether it was N.W.A. and arresting them at their show in Detroit. The FBI sending letters, whether it is the creation of hip-hop task force in various cities. Whether it’s the constant harassment of artists. That has been the narrative and that continues to be the narrative today, particularly as police expand these gang units. These units are watching, listening and treating rap music like its criminal evidence. So, as long as they are doing that regularly, I don’t see a whole lot of room for collaboration between artists and police, but that largely rest with the police. They are the antagonist in the story.

You open your book with the story of former No Limit Records artist, Mac and his trial. What issues do you have with the way his case was handled in court and the fact that he still sits in prison?

Erik Nielson: I’ll start with this, when I talk about this issue, one of the things that I try to make clear is that, in writing the book, we are not trying to asset the innocence of any of the people we are talking about in any of these cases. We’re not trying to say that somebody did or didn’t do it. What we’re trying to say is that they are entitled to a fair trial. That’s very hard to get once rap lyrics are being introduced. But there’s one exception to that, and that is, Mac. Mac is a case where I am absolutely certain that he is innocent. That he did not commit this crime. The evidence does not point anywhere near him and that’s why we began to focus on him. As I did more and more research, and I think it started because of, Angelique [Phipps]. I vaguely knew about this case, but it was only when she reached out and I started working with other journalists did I understand the details of it. And it just got worse and worse and worse. And so, I opened with that case because I see it as one of the most egregious injustices, I’ve ever seen up close. His continuing to sit there repeats that injustice every day. It was a fitting case, simply because of how frightening it was.

Would it just be easier to advise rappers to tone it down, be mindful of what they say and strip some of the purity of their artform away? Or do you feel that they can stay true to their storytelling and the legal system and justice system has to be the ones to get it right?

Erik Nielson: That is a really good question. It gets right to the heart of it. It’s a good question partly because the answer is difficult. I believe very strongly that it is the police and law enforcement who need to do their part to understand this genre. Just as they have done their part to understand every other genre that has violence, whether it’s horror films, gangster novels, gangster films, country music. Law enforcement has proven itself time and time again capable of understanding art. They are just choosing not to understand rap music. It’s hard for me to say to a young artist, “Hey, take out some of the violence. Take out some of the stuff that police might find offensive just to be safe.” Because we don’t ask that of any other artists. That’s what I say as an academic and just somebody thinking about it in an artistic sense. However, as a father, as a realist, I understand why some people’s impulse is to say to guys, “Hey, at least put a disclaimer at the beginning of the video that the guns are props.” At least take a few steps because you know the police are watching and they have always been watching. They are now more than ever, particularly with the explosion of social media use. I don’t think they should have to change their art one bit, but I understand why that would be the commonsense advice you might give to somebody. That’s the best answer that I can give you.

And I do get the purpose of the book. If you have Robert De Niro on trial prosecuting him for things he said in the movie, “Scarface,” or his actions in, “Casino,” or “Goodfellas.” I look at it like the pro wrestling business. Those guys play a character. Imagine having them on trial as if they are that character. So, I get it.

Erik Nielson: I appreciate the wrestling comparison because it’s one that I use often when I testify. Especially when I’m testifying in an area where I know they don’t like rap, but they probably do like wrestling (laughing). But I think the same point, right. These are guys… and it’s a lot like a rap performance. These are guys who have stage names, they engage in feuds that extend outside of the ring, they rarely break character, so you often don’t know the given name of a wrestler. You know his wrestling name only. And it’s a lot like gangster rap. In wrestling, there is some reality to it. There is two big guys and they really are in a ring going after each other, but the stuff that you pay to go see, the most violent stuff… that’s fake. That’s largely made up. It’s a performance. Just understanding rap as a performance goes a long way. It helps people understand that you can’t treat it literally and it certainly shouldn’t be introduced as evidence in a criminal case. I don’t see how it has any usefulness at all. It is just likely to inflame and prejudice a jury, which is of course why prosecutors are introducing it in the first place.

You have collaborated with, Killer Mike. If you don’t know, Killer Mike, you could certainly interpret that name is so many different ways.

Erik Nielson: Absolutely! And the funniest part about it or the most appropriate or fitting part is that, his stage name is, Killer Mike, it’s because he kills on the mic. We all understand what that means, but people could easily misinterpret that and not understand it. For example, if he’s criticized for having a song that’s anti-police, people will start to connect him. He’s Killer Mike, he’s anti-cop, they don’t know that his father was a police officer, and that he has great respect for law enforcement. The point that he has made in the past that sticks with me is, if his young children understands that, Killer Mike doesn’t mean that he’s actually a killer, if they can figure that out quickly, there is no reason why law enforcement can’t also. So, the fact that they claim ignorance starts to get tough to believe. It starts to feel like it’s intentional.

I can’t wait to read the book, “Rap On Trial.” Is there anything else you would like to add?

Erik Nielson: Thank you so much for taking this time. I really appreciate it.

Tweet