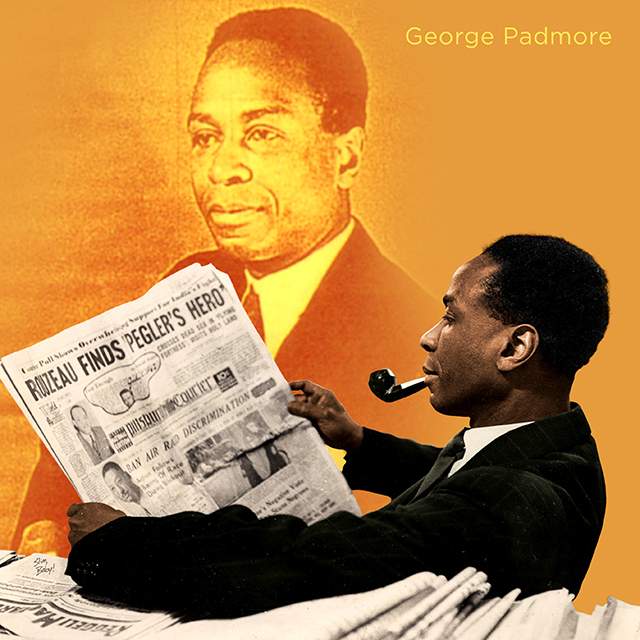

Black History Month art series by artist Adam Hernandez: Day 13 George Padmore

George Padmore (28 June 1903 – 23 September 1959), born Malcolm Ivan Meredith Nurse in

Trinidad, was a leading Pan-Africanist, journalist, and author. He left Trinidad in 1924 to study

medicine in the United States, where he also joined the Communist Party.

From there he moved to the Soviet Union, where he was active in the party, and working on

African independence movements. He also worked for the party in Germany but left after the

rise of the Nazis in the 1930s. He left the Communist Party in 1934 because of the abuses and

widespread purges under Stalinism. He continued to support socialism.

Padmore lived for a time in France, before settling in London. Toward the end of his life he

moved to Accra, Ghana.

Malcolm Ivan Meredith Nurse, better known by his pseudonym George Padmore, was born on

28 June 1903 in Arouca District, Tacarigua, Trinidad, then part of the British West Indies. His

paternal great-grandfather was an Asante warrior who was taken prisoner and sold into slavery

at Barbados, where his grandfather was born. His father, James Hubert Alfonso Nurse, was a

local schoolmaster who had married Anna Susanna Symister of Antigua, a naturalist.

In 1924, he travelled to the United States to take up medical studies at Fisk University, a

historically black college in Tennessee. Nurse subsequently registered at New York University

but soon transferred to Howard University.

During his college years, Nurse became involved with the Workers (Communist) Party. When

engaged in party business, he adopted the name George Padmore (compounding the Christian

name of his father-in-law, Constabulary Sergeant-Major George Semper, and the surname of

the friend who had been his best man, Errol Padmore).

Padmore officially joined the Communist Party in 1927 (when he was in Washington, DC) and

was active in its mass organization targeted to black Americans, the American Negro Labor

Congress.

Padmore, an energetic worker and prolific writer, was tapped by Communist Party trade union

leader William Z. Foster as a rising star. He was taken to Moscow to deliver a report on the

formation of the Trade Union Unity League to the Communist International (Comintern) later in

1929. Following his presentation, Padmore was asked to stay on in Moscow to head the Negro

Bureau of the Red International of Labour Unions (Profintern). He was elected to the Moscow

City Soviet, the Soviet (council) of the capital city, which was a workers’ council.

As head of the Profintern’s Negro Bureau, Padmore helped to produce pamphlet literature and

contributed articles to Moscow’s English-language newspaper, the Moscow Daily News.

As a deputy of the Moscow soviet, Padmore had served on the commission to investigate the

[1930 racial] assault on [Robert] Robinson [in Stalingrad]…. Even after he had renounced

Communism in the mid-1930s, Padmore continued until his death in 1959 to cite the trial of

Robinson’s assailants as evidence that the USSR was the only country that had effectively

eradicated racial discrimination.

In July 1930, Padmore was instrumental in organizing an international conference in Hamburg,

Germany. It launched a Comintern-backed international organization of black labour

organizations called the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (ITUCNW).

Padmore lived in Vienna, Austria, during this time, where he edited the monthly publication of

the new group, The Negro Worker.

In 1931, Padmore moved to Hamburg and accelerated his writing output, continuing to produce

the ITUCNW magazine and writing more than 20 pamphlets in a single year. This German

interlude came to an abrupt close by the middle of 1933, however, as the offices of the Negro

Worker were ransacked by ultra-nationalist gangs following the Nazi seizure of power. Padmore

was deported to England by the German government, while the Comintern placed the ITUCNW

and its Negro Worker on hiatus in August 1933.

Disillusioned by what he perceived as the Comintern’s flagging support for the cause of the

independence of colonial peoples in favor of the Soviet Union’s pursuit of diplomatic alliances

with the colonial powers, Padmore abruptly severed his connection with the ITUCNW late in the

summer of 1933. The Comintern’s disciplinary body, the International Control Commission

(ICC), asked him to explain his unauthorized action. When he refused to do so, the ICC

expelled him from the Communist movement on 23 February 1934.

As a result of his membership in the Communist Party and working for it in the Soviet Union and

Germany, Padmore was barred from re-entry into the United States. He was a non-citizen and

the government did not want to admit known communists.

Although alienated from Stalinism, Padmore remained a socialist. He sought new ways to work

for African independence from imperial rule. Relocating to France, where Garan Kouyaté was

an ally from his Comintern days, Padmore began to write a book: How Britain Rules Africa. With

the help of former American heiress Nancy Cunard, he found a London agent and, eventually, a

publisher (Wishart). It published the book in 1936, the year the publisher became Lawrence and

Wishart, known to be sympathetic to communists. Publication of books by black men at that time

was rare in the United Kingdom. A Swiss publisher distributed a German translation in

Germany.

In 1934 Padmore moved to London, where he became the centre of a community of writers

dedicated to pan-Africanism and African independence. His boyhood friend C. L. R. James, also

from Trinidad, was already there, writing and publishing. James had started International African

Friends of Ethiopia in response to Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia. That organization developed into

the International African Service Bureau (IASB), which became a centre for African and

Caribbean intellectuals’ anti-colonial activity. Padmore was chair, the Barbadian trade unionist

Chris Braithwaite was its organising secretary, and James edited its periodical, International

African Opinion. Ras Makonnen from British Guiana handled the business end. Other key

members included Jomo Kenyatta from Kenya and Amy Ashwood Garvey.

As Carol Polsgrove has shown in Ending British Rule in Africa: Writers in a Common Cause,

Padmore and his allies in the 1930s and 1940s—among them C. L. R. James, Kenya’s Jomo

Kenyatta, the Gold Coast’s Kwame Nkrumah and South Africa’s Peter Abrahams—saw

publishing as a strategy for political change. They published small periodicals, which were

sometimes seized by authorities when they reached the colonies. They published articles in

other people’s periodicals, for instance, the Independent Labour Party’s New Leader. They

published pamphlets. They wrote letters to the editor; and, thanks to the support of publisher

Fredric Warburg (of Secker & Warburg), they published books. Warburg brought out Padmore’s

Africa and World Peace (1937), as well as books by both Kenyatta and James. In a Foreword to

Africa and World Peace, Labour politician Sir Stafford Cripps wrote: “George Padmore has

performed another great service of enlightenment in this book. The facts he discloses so

ruthlessly are undoubtedly unpleasant facts, the story which he tells of the colonization of Africa

is sordid in the extreme, but both the facts and the story are true. We have, so many of us, been

brought up in the atmosphere of ‘the white man’s burden’, and have had our minds clouded and

confused by the continued propaganda for imperialism that we may be almost shocked by this

bare and courageous exposure of the great myth of the civilizing mission of western

democracies in Africa.” The Biographical Note on the cover describes Padmore as European

correspondent for the Pittsburgh Courier, Gold Coast Spectator, African Morning Post, Panama

Tribune, Belize Independent and Bantu World.

After Padmore’s death, Kwame Nkrumah paid tribute to him in a radio broadcast: “One day, the

whole of Africa will surely be free and united and when the final tale is told, the significance of

George Padmore’s work will be revealed.” In the Pittsburgh Courier, George Schuyler said

Padmore’s writings had been “an inspiration to the men who dreamed of a free Africa”.

Padmore’s physician friend, Cedric Belfield Clarke, wrote the obituary that ran in The Times,

describing Padmore as a writer who wrote books and studied them.

After a funeral service at a London crematorium, Padmore’s ashes were buried at

Christiansborg Castle in Ghana on 4 October 1959. The ceremony was broadcast in the USA by

NBC television. As C. L. R. James wrote,

“…eight countries sent delegations to his funeral in London. But it was in Ghana that his ashes

were interred and everyone says that in this country, famous for its political demonstrations,

never had there been such a turnout as that caused by the death of Padmore. Peasants from

far-flung regions who, one might think, had never even heard his name, managed to find their

way to Accra to pay a final tribute to the West Indian who spent his life in their service”

Trinidad, was a leading Pan-Africanist, journalist, and author. He left Trinidad in 1924 to study

medicine in the United States, where he also joined the Communist Party.

From there he moved to the Soviet Union, where he was active in the party, and working on

African independence movements. He also worked for the party in Germany but left after the

rise of the Nazis in the 1930s. He left the Communist Party in 1934 because of the abuses and

widespread purges under Stalinism. He continued to support socialism.

Padmore lived for a time in France, before settling in London. Toward the end of his life he

moved to Accra, Ghana.

Malcolm Ivan Meredith Nurse, better known by his pseudonym George Padmore, was born on

28 June 1903 in Arouca District, Tacarigua, Trinidad, then part of the British West Indies. His

paternal great-grandfather was an Asante warrior who was taken prisoner and sold into slavery

at Barbados, where his grandfather was born. His father, James Hubert Alfonso Nurse, was a

local schoolmaster who had married Anna Susanna Symister of Antigua, a naturalist.

In 1924, he travelled to the United States to take up medical studies at Fisk University, a

historically black college in Tennessee. Nurse subsequently registered at New York University

but soon transferred to Howard University.

During his college years, Nurse became involved with the Workers (Communist) Party. When

engaged in party business, he adopted the name George Padmore (compounding the Christian

name of his father-in-law, Constabulary Sergeant-Major George Semper, and the surname of

the friend who had been his best man, Errol Padmore).

Padmore officially joined the Communist Party in 1927 (when he was in Washington, DC) and

was active in its mass organization targeted to black Americans, the American Negro Labor

Congress.

Padmore, an energetic worker and prolific writer, was tapped by Communist Party trade union

leader William Z. Foster as a rising star. He was taken to Moscow to deliver a report on the

formation of the Trade Union Unity League to the Communist International (Comintern) later in

1929. Following his presentation, Padmore was asked to stay on in Moscow to head the Negro

Bureau of the Red International of Labour Unions (Profintern). He was elected to the Moscow

City Soviet, the Soviet (council) of the capital city, which was a workers’ council.

As head of the Profintern’s Negro Bureau, Padmore helped to produce pamphlet literature and

contributed articles to Moscow’s English-language newspaper, the Moscow Daily News.

As a deputy of the Moscow soviet, Padmore had served on the commission to investigate the

[1930 racial] assault on [Robert] Robinson [in Stalingrad]…. Even after he had renounced

Communism in the mid-1930s, Padmore continued until his death in 1959 to cite the trial of

Robinson’s assailants as evidence that the USSR was the only country that had effectively

eradicated racial discrimination.

In July 1930, Padmore was instrumental in organizing an international conference in Hamburg,

Germany. It launched a Comintern-backed international organization of black labour

organizations called the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (ITUCNW).

Padmore lived in Vienna, Austria, during this time, where he edited the monthly publication of

the new group, The Negro Worker.

In 1931, Padmore moved to Hamburg and accelerated his writing output, continuing to produce

the ITUCNW magazine and writing more than 20 pamphlets in a single year. This German

interlude came to an abrupt close by the middle of 1933, however, as the offices of the Negro

Worker were ransacked by ultra-nationalist gangs following the Nazi seizure of power. Padmore

was deported to England by the German government, while the Comintern placed the ITUCNW

and its Negro Worker on hiatus in August 1933.

Disillusioned by what he perceived as the Comintern’s flagging support for the cause of the

independence of colonial peoples in favor of the Soviet Union’s pursuit of diplomatic alliances

with the colonial powers, Padmore abruptly severed his connection with the ITUCNW late in the

summer of 1933. The Comintern’s disciplinary body, the International Control Commission

(ICC), asked him to explain his unauthorized action. When he refused to do so, the ICC

expelled him from the Communist movement on 23 February 1934.

As a result of his membership in the Communist Party and working for it in the Soviet Union and

Germany, Padmore was barred from re-entry into the United States. He was a non-citizen and

the government did not want to admit known communists.

Although alienated from Stalinism, Padmore remained a socialist. He sought new ways to work

for African independence from imperial rule. Relocating to France, where Garan Kouyaté was

an ally from his Comintern days, Padmore began to write a book: How Britain Rules Africa. With

the help of former American heiress Nancy Cunard, he found a London agent and, eventually, a

publisher (Wishart). It published the book in 1936, the year the publisher became Lawrence and

Wishart, known to be sympathetic to communists. Publication of books by black men at that time

was rare in the United Kingdom. A Swiss publisher distributed a German translation in

Germany.

In 1934 Padmore moved to London, where he became the centre of a community of writers

dedicated to pan-Africanism and African independence. His boyhood friend C. L. R. James, also

from Trinidad, was already there, writing and publishing. James had started International African

Friends of Ethiopia in response to Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia. That organization developed into

the International African Service Bureau (IASB), which became a centre for African and

Caribbean intellectuals’ anti-colonial activity. Padmore was chair, the Barbadian trade unionist

Chris Braithwaite was its organising secretary, and James edited its periodical, International

African Opinion. Ras Makonnen from British Guiana handled the business end. Other key

members included Jomo Kenyatta from Kenya and Amy Ashwood Garvey.

As Carol Polsgrove has shown in Ending British Rule in Africa: Writers in a Common Cause,

Padmore and his allies in the 1930s and 1940s—among them C. L. R. James, Kenya’s Jomo

Kenyatta, the Gold Coast’s Kwame Nkrumah and South Africa’s Peter Abrahams—saw

publishing as a strategy for political change. They published small periodicals, which were

sometimes seized by authorities when they reached the colonies. They published articles in

other people’s periodicals, for instance, the Independent Labour Party’s New Leader. They

published pamphlets. They wrote letters to the editor; and, thanks to the support of publisher

Fredric Warburg (of Secker & Warburg), they published books. Warburg brought out Padmore’s

Africa and World Peace (1937), as well as books by both Kenyatta and James. In a Foreword to

Africa and World Peace, Labour politician Sir Stafford Cripps wrote: “George Padmore has

performed another great service of enlightenment in this book. The facts he discloses so

ruthlessly are undoubtedly unpleasant facts, the story which he tells of the colonization of Africa

is sordid in the extreme, but both the facts and the story are true. We have, so many of us, been

brought up in the atmosphere of ‘the white man’s burden’, and have had our minds clouded and

confused by the continued propaganda for imperialism that we may be almost shocked by this

bare and courageous exposure of the great myth of the civilizing mission of western

democracies in Africa.” The Biographical Note on the cover describes Padmore as European

correspondent for the Pittsburgh Courier, Gold Coast Spectator, African Morning Post, Panama

Tribune, Belize Independent and Bantu World.

After Padmore’s death, Kwame Nkrumah paid tribute to him in a radio broadcast: “One day, the

whole of Africa will surely be free and united and when the final tale is told, the significance of

George Padmore’s work will be revealed.” In the Pittsburgh Courier, George Schuyler said

Padmore’s writings had been “an inspiration to the men who dreamed of a free Africa”.

Padmore’s physician friend, Cedric Belfield Clarke, wrote the obituary that ran in The Times,

describing Padmore as a writer who wrote books and studied them.

After a funeral service at a London crematorium, Padmore’s ashes were buried at

Christiansborg Castle in Ghana on 4 October 1959. The ceremony was broadcast in the USA by

NBC television. As C. L. R. James wrote,

“…eight countries sent delegations to his funeral in London. But it was in Ghana that his ashes

were interred and everyone says that in this country, famous for its political demonstrations,

never had there been such a turnout as that caused by the death of Padmore. Peasants from

far-flung regions who, one might think, had never even heard his name, managed to find their

way to Accra to pay a final tribute to the West Indian who spent his life in their service”

Adam Hernandez | Black History Art Series

Tweet